Director of Saitama Children’s Zoo, Rieko Tanaka

Of the seven zoos across Japan that currently house koalas, it is the Saitama Children’s Zoo that has a reputation for their repeated success in not only caring for, but also breeding, the furry marsupial. The zoo is also home to a range of other interesting Australian animals – kangaroos, wallabies and quokkas. The zoo’s Director, Rieko Tanaka, has visited Australian zoos as well as observed these animals in the wild. We spoke to Ms Tanaka about how raising these animals has informed her view of the future of wild animals and about the role that zoos should play.

Raising native Australian animals such as koalas and quokkas

Q: Could you please tell us a little about your current job?

A: I oversee the entire management of the Saitama Children’s Zoo, from caring for the animals, their display and business operations. As Director, I spend a lot of my time training and managing zookeepers. I also appear on the NHK radio program Children’s Science Advice Hotline answering questions, and also giving lectures on topics such as “The work of a zookeeper” and “The role of zoos.”

There has been a trend toward animal welfare across the world in recent years, meaning that zoos are charged with caring for their animals in a way that ensures they have a healthy, rich life. The English word ‘enrichment’ is often used in this context. This means, for example, not merely placing food in a plate when feeding certain species, but rather putting the food up high, or hiding it so that the animal has to look for it. This is not because we want to tease the animals. Rather, it is an attempt to bring out the same behaviour that they would display in the wild, so that they can rely upon their own instincts.

Q: There are a lot of Australian animals at the Saitama Children’s Zoo. What Australian animals do you currently have?

A: We have eight varieties of marsupials alone, ranging from koalas, kangaroos and wallabies to sugar gliders, feathertail gliders and quokkas. Apart from these, we also have unique Australian birds, such as parrots and emus. We keep many of our Australian animals in the East Wing of the zoo, which is a great place to learn about the characteristics and lifestyles of these animals.

The Koala enclosure is full of informative signs.

Q: What was the reason that the zoo became so active in keeping Australian animals?

A: The first koalas came to Japan in 1984. At that time, Tama Zoo in Tokyo, the Nagoya Higashiyama Zoo in Aichi, and the Hirakawa Zoo in Kagoshima each received two koalas. Saitama Children’s Zoo subsequently received two male koalas in 1986, followed by four females in 1987.

The background to this coming to fruition is that Saitama Prefecture has a sister-state relationship with Queensland. Later on, we received kangaroos, as well as some Australian birds related to geese, meaning that the East Wing slowly became our area for Australian animals.

Yellow tailed rock wallabies kept at the zoo’s East Wing

Q: Can you talk to the charms of Australia’s endemic wildlife, such as koalas and quokkas?

A: More than anything is, it has to be that they have pouches. Marsupials are full of originality – they need to be looked after in a particular way and have a unique breeding method. Did you know that koalas are also marsupials? Our zoo has rich experience keeping small marsupials, and our skill in this area has been praised even from the Australian side.

One outcome of this record is that the Featherdale Sydney Wildlife Park gave us permission to take on the care of four quokkas in March 2020, coinciding with the 40th anniversary of our founding. Quokkas are known as the “happiest animals in the world.” The vertically-facing structure of their mouth combined with the fact they have very developed jaw muscles from eating tough grass, makes them look as if they are constantly smiling. This has made them a global hit on social media.

There are about 3,000 wild quokkas living on the Australian mainland, and another 10,000-12,000 living on Rottnest Island, which lies southwest off the continent’s coast. We have succeeded in breeding quokkas every year, and now we are home to a happy family of eight quokkas, which is double what we started with.

Quokkas - a small marsupial known as “the happiest animals in the world.”

High awareness of conserving Australia’s native animals

Q: What is difficult about keeping Australian animals?

A: Australia is very aware of the conserving their unique wildlife, so there are very strict standards that must be met when importing these native animals from Australia. In our case, we had to submit maps showing that we have enough space to keep the animals, a plan for their management and also data about the annual temperature and humidity for Higashi Matsuyama City, which is where our zoo is located.

Another difficulty in raising koalas and quokkas is that each and every one has a completely different personality. There are lazy ones, aggressive ones and even neurotic ones. You have to consider what is best for each and every individual, meaning that it is a daily struggle to ensure that they have the rich environment they need to thrive.

Koalas kept here are of all ages and personalities.

Q: How would you recommend visitors enjoy your zoo?

A: We have tried to ensure that a visit to our zoo is not just about seeing the animals, but that it is also an opportunity to engage with Australian culture. For example, zookeepers have created artworks dotted around the animal display areas that are inspired by Australian art.

We also have an Australia Festival once a year. We have special souvenirs and food for sale, as well as Australia-themed events. At previous festivals, we have had workshops about making and playing your own didgeridoo, which is a traditional Australian First Nations instrument. We have also had face painting, and a stamp rally where kids go around the zoo in search of all our Australian animals. We weren’t able to hold the festival during the COVID period, but were able to restart the event in 2023.

Everything started with a book by Mistuko Masui called “My Record of Animals”

Q: Let’s look back a little into the past. What made you want to work at a zoo?

A: I always loved animals and since I was in primary school I’d always wanted to become a zookeeper. I love all animals, from dogs and cats to frogs and snakes. I’d often catch small animals and insects on my way back from school and take them home with me. I think I was the strange kid in my neighbourhood!!

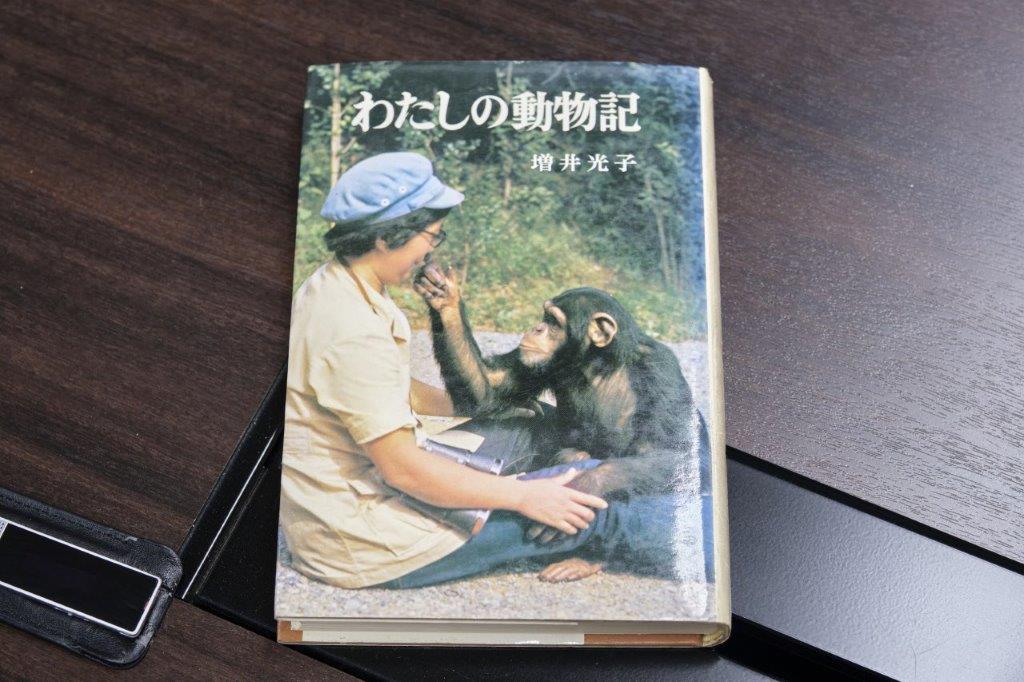

What cemented my desire to become a zookeeper was a book that I received when I was in Year five at primary school called “My record of animals” by the Director of Ueno Zoo, Mitsuko Masui. Having read this book I felt that being a zookeeper would be a lot of fun.

The book “My record of animals” (Mitsuko Masui, Poplar Publishing) inspired M Tanaka to become a zookeeper

After that, I read a lot of books about animals in secondary school. I think I read every last book on animals in our library. My mother also used to sell picture books, and she often told me that I should spend money on buying books. At the time, probably about 1980, there was a popular TV program called “Wild Kingdom” that I remember watching regularly.

I was in Year eleven when I first visited the Saitama Children’s Zoo, probably in 1980 when it first opened in the area where I grew up. I was thrilled that my dream place had opened up in my hometown! I loved it so much that I went directly to ask that they let me work for them in my spare time, even though they weren’t recruiting! That’s how I started to help the zookeepers.

After that, I was concerned with which university would be best for me to learn how to become a zookeeper. I phoned the then Director of Tobu Zoo to get advice about where to study. The advice I got was to study livestock science at university, so in the end I went to Tokyo Agriculture University to study at the Department of Animal Science in the Faculty of Agriculture.

I continued working part time at the Saitama Children’s Zoo during university. I would actually skip class for up to two weeks straight whenever they were temporarily short-staffed. Thanks for the fact I got to know everyone, around the time I was about to graduate they were kind enough to let me know that Saitama Parks – which manages the zoo – were recruiting for a single staff member, which I luckily got. That was 1986 - I entered the zoo at the same time as its very first koala arrived.

Whoever looks after koalas must be a eucalyptus expert

Q: So you had a connection to koalas ever since you were hired. How were you involved with other Australian animals since that time?

A: Six years after I was hired they assigned me to oversee the koalas and other Australian animals. I was so excited, but my predecessor in the role said that “whoever looks after koalas must be a eucalyptus expert.” Of course, anyone looking after koalas has to learn the twenty or so varieties of eucalyptus that koalas eat. That is much harder than learning to recognise the individual koalas we had. Each koala has its preferred variety, so I had to prepare the right variety for the right individual. What’s more, the variety that one koala liked today it might turn up its nose to the next. It was so tricky.

When I got to work in the mornings, I would go through the video recordings from the night before to see how much each koala had moved, where they had had a drink and every other detail. At that time, the person in charge of koalas would spend almost all their day watching the videos and checking on the eucalyptus.

I’d heard these horror stories before I began, so was worried about whether I was cut out to be in charge of koalas. But once I started doing it, it was really interesting. We were then successful at breeding koalas, but we knew nothing about the birth or the growth of the baby, which only piqued my interest in koalas further. That is when I began to get interested in seeing for myself how wild Australian animals lived.

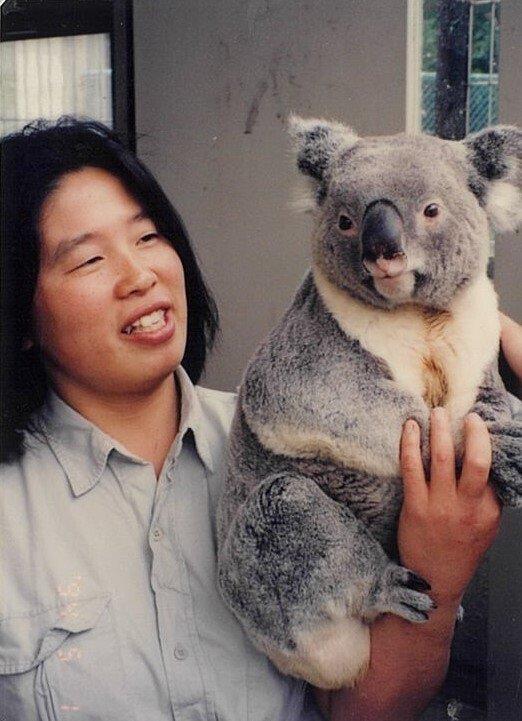

A picture from around 1991 when Ms Tanaka was in charge of Australian animals, including koalas

Q: Have you ever been to Australia to take a look at how animals are kept there?

A: From the 1990s until the 2000s, I would regularly go to Australia to observe wild animals as well as visit zoos. It wasn’t an official study tour, but just my own private travel. I went to Kakadu National Park in the Northern Territory, as well as went to observe how wild birds, koalas and quokkas lived.

I went with a friend to camp in Kakadu National Park and was surrounded by wild animals. There were just so much nature and so many living things around me. That’s what Australian national parks are like. There are also areas in Australia where, for some reason, koalas live in high density groupings. These places are not made public, so I had to rely on media reports and Google Maps to identify where to go. I was told that that particular place was home to eucalyptus trees with highly nutritious leaves thanks to the rich soil of that area.

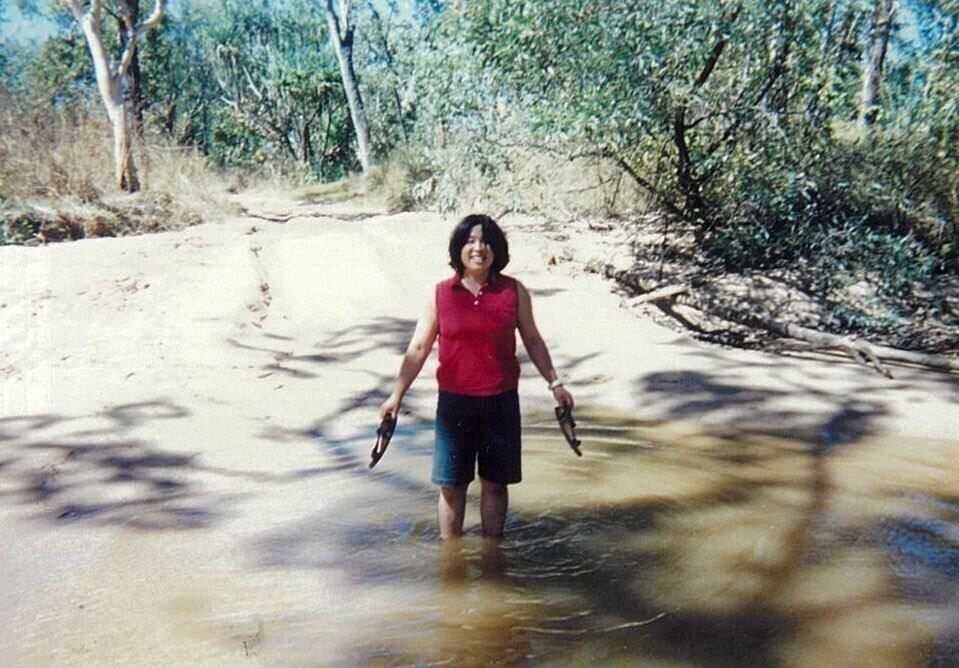

In Kakadu National Park (1999)

Of Australian’s many zoos, the one that I like the most is Healesville Sanctuary near Melbourne, which blends in with its surrounding environment so that you come across animal displays dotted throughout its verdant grounds. I learnt a lot from their zookeeping methods and display techniques. I also would go in search of a particular animal – for example I went to a zoo in Perth specifically to see a numbat. I would often become friends with the local zookeepers and exchange information with them. Being in the same industry, it’s easy to empathise with one another. And to do that, I just had to learn English. A lot of the literature about zookeeping is in English too. There was a time when I was really serious about going to English language classes.

At a friend’s farm in Australia (1999)

Connections in Australia vital to exchange

Q: Do you exchange information or get instructions about specific animals, like koalas or quokkas?

A: When it comes to the animals that were formally gifted to us from Australia such as koalas and quokkas, there is a requirement for the zookeepers in charge to undergo training for a set period of time. Zookeepers, along with vets, spend about a week in Australia getting trained up. One of my zookeeper colleagues spent over a month there in training. Of course, all the training is in English. They teach you a lot of detail, including how much to feed them, what their enclosure should be like, etc.

As I mentioned before, we have signed agreements with states and zoos who have provided us with the koalas, and we must operate in line with those requirements. We also follow the management techniques taught to us by Australian zoos, so our methods differ slightly from those employed by other Japanese zoos. That’s how exacting koala management is.

Australians are much more used to caring for young wild animals than Japanese people are, so they are accustomed to all this. I think they naturally have a sense about caring for animals while preserving their wildness. For example, in Australian bookstores, you can find books about how to care for marsupials that you may have picked up from somewhere. That surprised me.

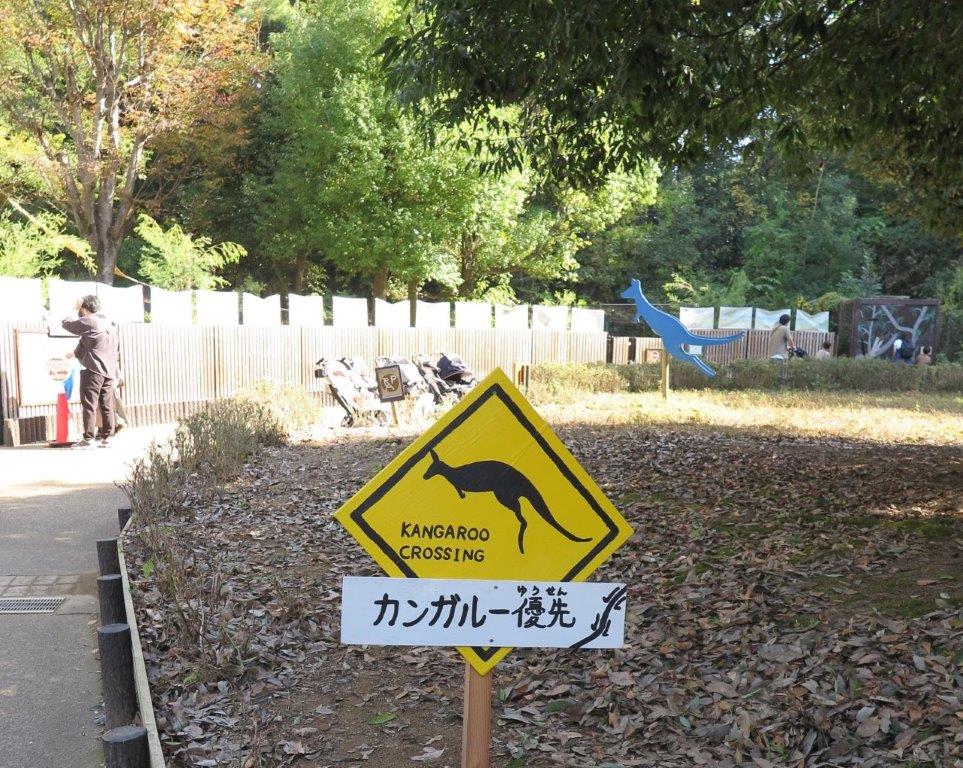

A unique sign in the East Wing, where Australian animals are kept

Next time you go to a zoo, keep a lookout for animal odours

Q: Staff at the zoo put out a lot of information about the animals in their care. What do you keep in mind with this messaging?

A: It’s important to put out messaging, which we do at Saitama Children’s Zoo via our website and also social media, such as Instagram and X (formerly Twitter). We also speak at a range of educational institutions, from primary schools, secondary school and all the way up to university.

The Saitama Children’s Zoo official website

We often speak about the conservation of wild animals as well as biodiversity, about how climate change is affecting wild animals all around the world. We hope that people will pass this information on to their family and friends.

More than anything, I hope that people come to zoos and notice the odours of the animals. Both koalas and giraffes have a very distinctive odour, which changes when they are in heat or not feeling well. Zookeepers need to be alert for this. Learning about animals with all five senses is great for kids.

Koalas and quokkas, which are mostly nocturnal animals, are more active on days that are a little overcast, rather than when it is sunny. That is a way to enjoy zoos even when the weather isn’t so good, and when the zoo isn’t as crowded. We don’t leave animals that are susceptible to heat outside when the temperature soars during the day. We ensure they have the freedom to come and go from air-conditioned rooms so that they can choose where is most comfortable for themselves. So, on some occasions, the animals may not come out to where you can see them. We don’t have many visitors who leave angry at this situation, as most understand. We want people to know that we put the animals first and do everything we can to ensure they live as pleasantly and freely as possible.

Koalas tend to spend a lot of time up trees.

Q: I believe you have an exchange program with the Yugambeh Museum in Queensland, funded by the Australia-Japan Foundation. How would you like to build relationships with Australians via caring for Australian animals?

A: During the COVID crisis in 2021, we held an online event with Yugambeh Museum about the culture of the Aboriginal people. Former President of the Queensland Zoo and Aquarium Association and former head of Dreamworld on the Gold Coast, Al Mucci, was a great help on this.

Associate Professor Steve Johnston from the School of Veterinary Science at the University of Queensland also gave us lectures about koala reproduction. This sort of event is something that we were able to do only thanks to the fact that we’ve build up relationships in Australia through keeping Australian animals like koalas and quokkas.

The Kangaroo area of the East Wing.

Now that COVID is behind us, we hope to have similar cultural exchange programs held in person. I hope this is a chance for Australians to also learn more about our zoo.

I hope to spark interest in biodiversity and the global environment

Q: What dreams or goals do you wish to achieve through keeping Australian animals, such as koalas and quokkas?

A: I hope to accept even more animals into the future while continuing to cherish the sister state relationship that Saitama Prefecture has with Queensland. Accepting animals from abroad isn’t easy – it isn’t unusual for planning to take as long as five years. Just as diversity is important amongst humans, I hope to contribute, even if just a little, to increasing the number of people who think deeply about biodiversity on a global scale after having encountered a range of animals at our zoo.

I might be repeating myself, but the areas available for wild animals in Australia is declining as a result of climate change and bushfires, etc. This is clear from the satellite pictures we have on display at the Koala enclosure. I want everyone to think deeply about the environmental and issues facing wild animals, lest we someday look back and say, “koalas once lived in the wild.” I especially want to see children come to the zoo if they have anything they want to know. Why not come in summer holidays to look for a topic for your summer research project. Stimulating conversations about topics such as biodiversity and the global environment is one extremely important role for zoos to fulfil.

The Saitama Children’s Zoo collected donations for the Australian bushfires of 2019-2020.

【Interview with the cooperation of 】

The Saitama Children’s Zoo in Higashi Matsuyama City is home to koalas, kangaroos, wallabies, quokkas and many other native Australian animals. Each year they hold an Australian Festival, which includes events about Australian culture.