Compared to British or American culture, many Japanese people are not yet familiar with Australian literature and theatre. But in recent years many works have started to receive global recognition. Recently, shows about Indigenous Australians, Asian migrants, and Japanese migrants have picked up interest, and have even been performed in Japan. Professor Sawada from Waseda University has researched Australian theatre and literature since the 1990s. He translates Australian plays and publishes the Australian Drama Series to show its appeal to the Japanese public. We interviewed Professor Sawada and discussed Australian theatre’s past, present, and future.

ー Professor Sawada, you have never stopped translating and publishing Australian plays. Please tell us about your work in Japan to showcase Australian theatres and movies.

I currently research Australian literature and theatre at Waseda University. I was once a researcher at the Institute of Australian Studies within the University as well. My interest in Australia was sparked during my childhood. My father, who was an English academic, was researching Australian and New Zealand English. We stayed in Sydney as a family for a short time, and the experiences I gained there have stuck with me since.

I eventually started studying English literature under the (then) First Department of Literature at Waseda University. However, at the time English literature studies were centred around British and American literature, and no one even thought about studying Australian literature. People would imagine koalas and kangaroos when Australia was mentioned. Although some visited the Gold Coast for their honeymoon, no student would consider learning about the local culture, let alone literature and theatre.

On the other hand, my father was working on a thick dictionary, titled the Encyclopaedic dictionary of Australian and New Zealand English and culture, which covers many events related to Oceanian culture and art. As I helped him, my interest towards Australia’s culture and history grew. I also started to question why Australia was not included in English-speaking cultural studies at universities.

Cover of the Encyclopaedic dictionary of Australian and New Zealand English

Following that, I began my postgraduate studies majoring in Theatre Studies at the Graduate School of Letters, Arts and Sciences, at Waseda University. I deepened my knowledge about Australia’s literature and theatres there. As I was about to start my PhD studies, I began to work as a research associate at the Waseda University’s Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum and spent my days reading Australian plays stored there. Among them was one play that gave me a big shock ... That was The floating world written by an Australian playwright, John Romeril.

This play explores the relationship between Japan and Australia during the Second World War. It is a very heavy story about a former Australian solider who was captured by the Imperial Japanese Armed Forces during the war suffering from his memories when he travels to Japan with his wife. I decided to translate this play because I thought Japanese people should know more about the war between Australia and Japan. I published the translation in 1993 as the first volume of the Australian Drama Series, which continues to this day.

After publication, in 1995, a Japanese version of The floating world was performed at the Tokyo Performing Arts Festival and Melbourne International Festival of the Arts. Simultaneously, a theatre troupe from Melbourne performed a play based on the atomic bombing of Nagasaki. It was a project aimed at sharing memories of the war by exchanging plays that were originally written in the other country’s language to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the end of World War II.

Cover of the Australian Drama Series vol. 1 with The floating world

Back then, many war-themed plays were performed in Japan to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the end of the war. However, the younger generations lacked interest and the response to The floating world [in Japan] was moderate. In contrast, Australia’s SBS reported the play on their news program and a newspaper published an article titled ‘This performance is equivalent to thousands of apologies’. I was surprised at the huge difference in responses towards memories of the war between Japan and Australia.

This performance was a big turning point for me. It gave me a sense of purpose; that I needed to introduce more Australian plays to the Japanese audience. I went on exchange to the University of Sydney right at this time, from 1995 to 1998, where I deepened my knowledge of Australian theatre at its home grounds. After that in 1998, I published a book titled A history of Australian film (Oceania Press).

Cover of A history of Australian film

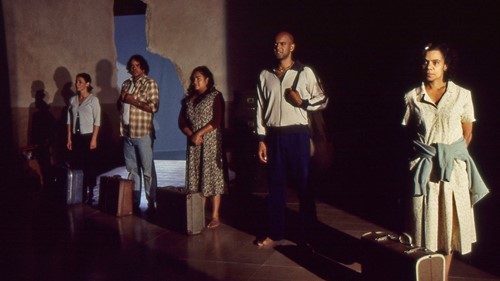

A memorable play I worked on after returning to Japan from Australia was an Indigenous play called Stolen, which was performed at the 2002 Tokyo International Arts Festival. This play is about the ‘Stolen Generation’, a period where Aboriginal children were taken from their families.

Indigenous issues are hard to visualise in Japan and are often regarded as a foreign issue. But once the issue was expressed as a performance, many in the audience considered it as their own matter. Personally, being able to work on the subtitles and performing both the original and Japanese version of the play in the same period was a memorable experience. I dwelled a lot on how we should introduce an Indigenous Australian play to Japan. Some people in the Australian theatre industry suggested we cast actors of Ainu heritage. The challenges I faced then continue to be an important research topic for me.

Later, in 2003, I contributed to the performance of an Indigenous play, Up the ladder, at Ancient Future: Australian Arts Festival Japan. It is a story about an Aboriginal ‘tent boxer’ at a side show boxing ring circuit progressing his career as a boxer.

During the Australia-Japan Year of Exchange in 2006, I was the chief executive of a drama festival called Dramatic Australia and progressed cultural exchange through Australian theatre. By this time, the earlier image of Australia [just] being a country of koalas and kangaroos faded. Instead, Australia was finally getting recognised as a country with diverse and deep culture.

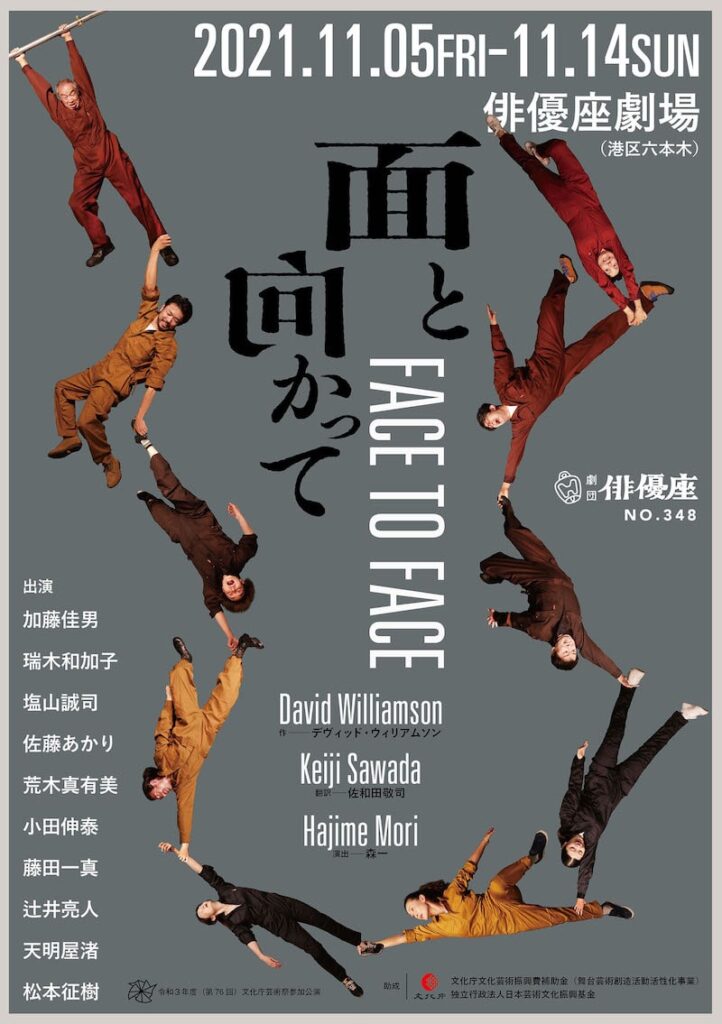

In 2021, I introduced a play centred around the theme of restorative justice, which is unique to Australia. This approach is incorporated into the judicial system, providing a framework in which perpetrators and victims can engage in dialogue in an effort to restore their relationship. A famous Australian playwright, David Williamson announced a trilogy that interviewed and explored the use of this system in practice. When two plays from the trilogy were performed in Japan, it received a great deal of attention.

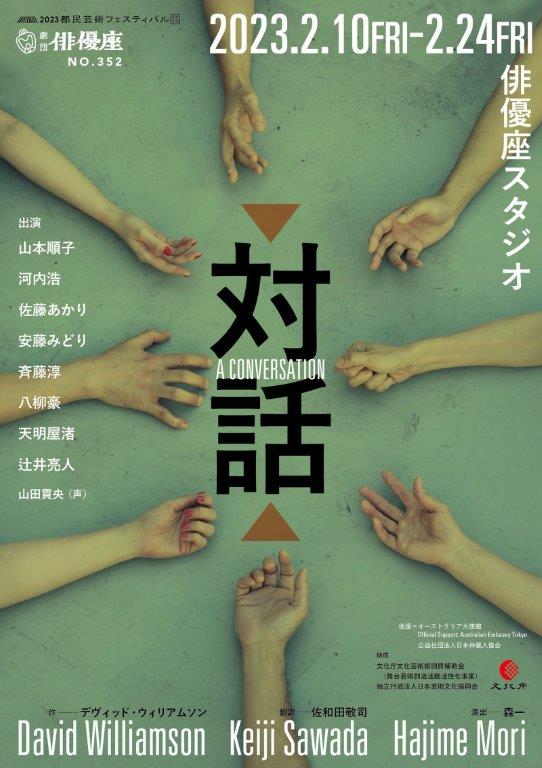

Posters of Face to Face and A Conversation by Haiyuza Theatre Company

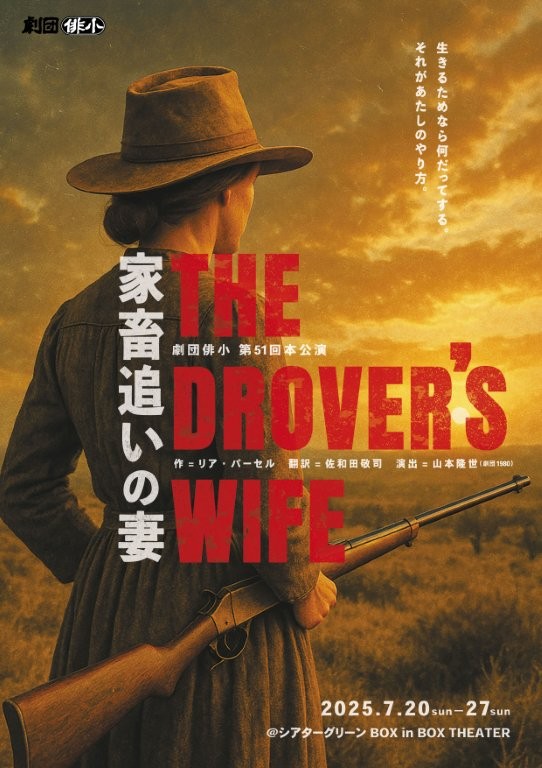

Further, I participated in a project for the Australian First Nations Film Festival that took place at Eurospace in Shibuya in February 2024. Here, we were able to showcase The drover’s wife: the legend of Molly Johnson, a film directed by an Aboriginal actor and playwright, Leah Purcell. The original play this film is based on was performed in Japan in July 2025.

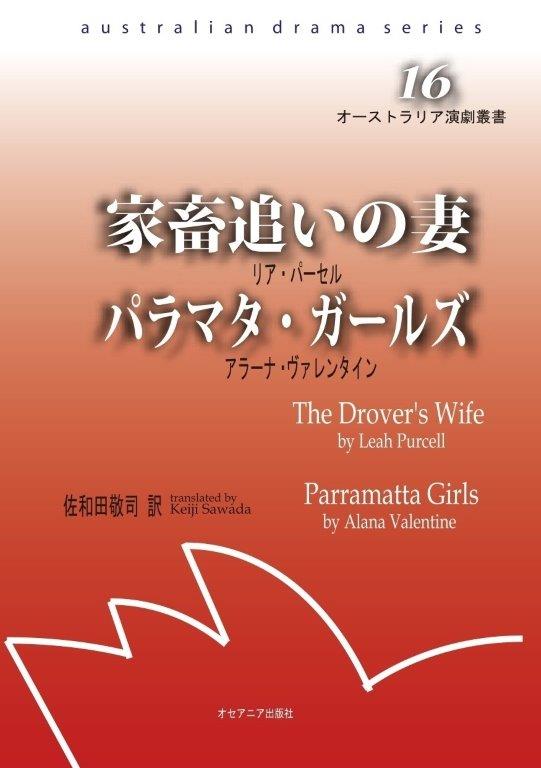

Cover of the Australian Drama Series vol. 16 with The drover's wife and Parramatta Girls

Leah Purcell

I’ve recently been working on introducing Yasukichi Murakami – through a distant lens, a play written by Mayu Kanamori, a photographer who was born in Japan and lives in Australia. This is a story about Yasukichi Murakami who migrated to Australia prior to the war. It is quite an interesting piece to understand the history of Australia-Japan relations.

I am currently working to publish a book about Yasukichi Murakami – through a distant lens with the funds I received from the Australia-Japan Foundation. I also plan to continue my work in showcasing Australian theatre and literature. I’m particularly interested in plays written by Asian-Australian scriptwriters.

ー Is there a particular field/category of Australian play, film or literature you specialise in?

I’m interested in modern plays that are based around the theme of Indigenous Australians or refugees. From my perspective, all Australian theatre can be described as modern theatre. When you reflect on the history of Australia, it was first established as a penal colony and prisoners and soldiers stood on stage to perform plays from the UK and Ireland. That is the beginning of Australian theatrical culture.

Even though magnificent theatre halls like the Sydney Opera House were constructed, up to the 1970s most performances [at these larger theatres] were British or American plays. Hardly any plays written by Australians were staged. On the other hand, plays that reflected voices of Australians started to be performed at smaller theatres in the 1960s. I think the wave that started then continues to this day.

Exploring the possibilities of cross-cultural theatres through translation is another theme I focus on. The play that influenced this was Stolen, which I mentioned earlier: a play that is focused on Indigenous Australians. I contributed to the large effort to bring and put on this play at the Tokyo International Arts Festival in 2002.

This performance is based around an Australian Government policy to remove Aboriginal children from their families, known as the ‘Stolen Generation’. The play is a signature piece written by Jane Harrison. She wrote after interviewing those directly impacted by the policy for six years. It features five children that lived during separate times over the 70 years the policy was in force. But in the play, they all live together in one facility and that really brings out the essence of tragedy.

Production still for "Stolen" (1998). L-R: Tammy Anderson as Anne, Stan Yarramunua as Sandy, Pauline Whyman as Shirley, Tony Briggs as Jimmy, Kylie Belling as Ruby. Photographer: Unknown

Production still for "Stolen" (1998). L-R: Tony Briggs as Jimmy, Pauline Whyman as Shirley, Kylie Belling as Ruby. Photographer: Unknown

I was responsible for translating this play before I handed over to the Rakuten theatre company to perform in Japan. After that, Ilbijerri Theatre Company and Melbourne-based Playbox Theatre Company performed their own original interpretation of the play with subtitles. This version was produced by an Indigenous playwright and artistic director, Wesley Enoch, who is also a board member at the Australia-Japan Foundation. By playing two interpretations of the same play at the same arts festival, they achieved ‘competitive collaboration.’

Scenes of the performance of Stolen by Rakutendan theatre company

Wesley Enoch

Credit Cassandra Hannagan

Wesley Enoch was in tears after he watched the Japanese version of the play. He recognised the passionate performance by the Japanese actors, but also said ‘It is impossible fully portray that character unless you have experienced discrimination as an Aboriginal person.’ In the Australian version, an Indigenous actor would share their family history after the show. The audience would see ‘a person impacted in front of them.’ I found a reality that cannot be conveyed just through translation. I remember that was when I sensed the limits and new possibilities of cross-cultural theatre.

The background to that was the history of Japanese-translated plays. In terms of modern Japanese theatre, a surge of Western plays entered Japan during a time only kabuki and bunraku puppet theatre existed. From there, actors started to accept and use expressions specific to the West (such as hugging or kissing) that they had never experienced before as a form of ‘Western style.’ In other words, Japan’s translated plays developed their own unique style.

In Japan this aesthetic style of translated plays has permeated into the audience to the point no one notices it anymore. No one finds it unnatural when a Japanese actor performs in overexaggerated speech for a Shakespearian play. This means that translated plays in Japan have completely embraced Western culture and made it a part of the form.

But I realised this is not necessarily the correct answer; and rather that there is space for discussion. The ‘competitive collaboration’ of Stolen helped me realise this. There is a significance to having an actor who shares the same societal experience as the character they are portraying stand in front of the audience. This is something that fundamentally changed my views on translated plays in Japan, to the point I wrote about it in my PhD thesis at Macquarie University (New South Wales).

Thanks to the efforts of people like Wesley Enoch, there are more places for Indigenous actors to shine in Australia. The Australian Government supports that and now there are Indigenous actors acting as a non-Indigenous characters in TV shows or plays. This is the result of the efforts of pioneers like Leah Purcell, the author of The drover’s wife, who I mentioned earlier, who wrote plays themselves, and opened many doors to roles. It is not simple political correctness; it is not just deciding on a quota and distributing roles by ethnicity.

With Wesley Enoch

With Leah Purcell, Director and Bain Stewart, Producer of the The drover’s wife: the legend of Molly Johnson

I took on the challenge of making a Japanese actor portray an Indigenous character in the Japanese performance of Stolen. By taking this approach in ‘competitive collaboration’, any objections can lead to thorough discussions. This experience can then become useful for future performances. I think I this gave me hints to expand the possibility of cross-cultural theatre from this experience.

ー Please tell us any episode that sparked your interest for Australian theatre and lead you to become deeply involved in it.

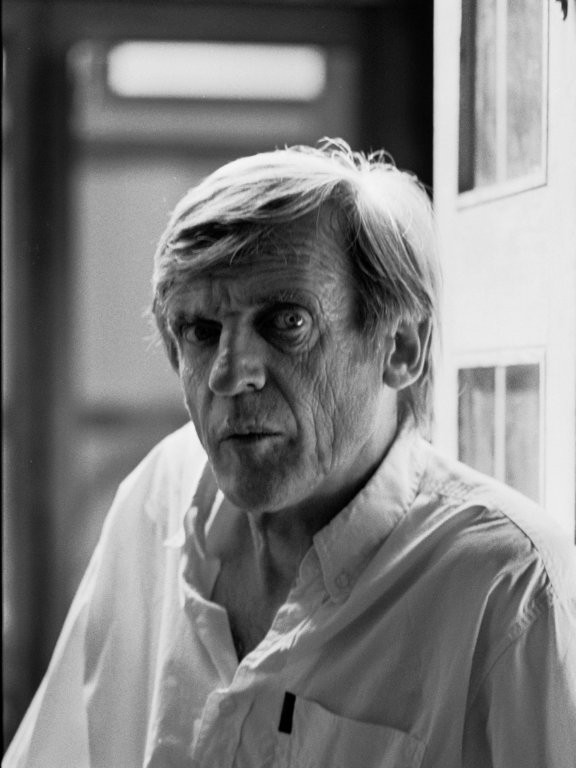

It has to be the Japanese performance of The floating world in 1995. Playwright John Romeril was impressed that a young person like myself was interested in this piece during a time only Japanese tourists visited Australia despite there being no apology for the war.

John Romeril

©Mayu Kanamori

This was a significant project as we were intersecting memories of the war from both countries on the 50th anniversary year of the end of World War II. It was a ‘theatrical exchange’ organised by producers of the Tokyo Performing Arts Festival and Melbourne International Festival of the Arts, and a challenge to perform each other’s war-themed plays in each other’s language.

My main role was to translate The floating world into Japanese. The story follows an Australian soldier who is traumatised by his experience as prisoner of war during World War II, and he eventually goes insane. After the war, he travels to Japan by ship with his wife. On the way there, he is tormented by the spirits of his friends who died from abuse by the Japanese Imperial Armed Forces. ‘Why must you go to Japan?’ they say … When the man arrives at the Port of Yokohama, he is sent to a psychiatric hospital, and that’s where the story ends.

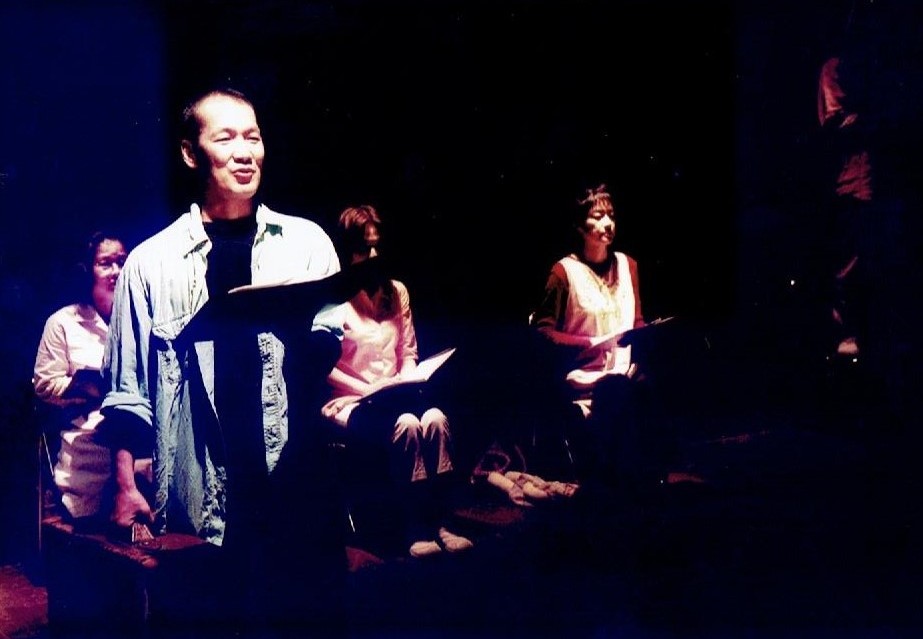

The Japanese performance involved actors from the Black Tent Theatre led by Makoto Sato, and even Youkiza, a well-established Edo-style marionette store with 390 years of history. During a scene where a lion dance puppet roamed the ship, a member of the Australian audience said, ‘I’ve never seen anything like it’.

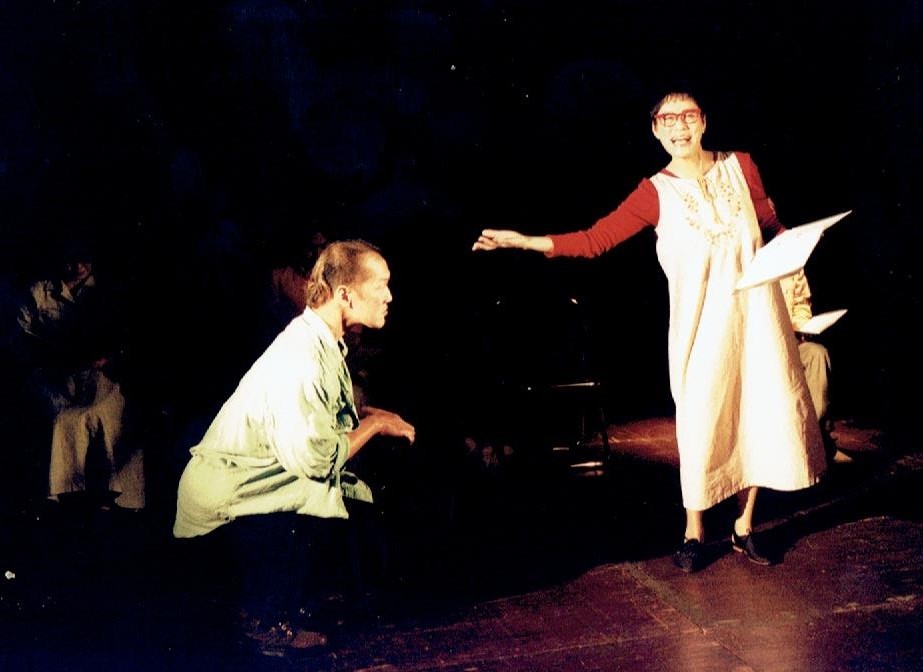

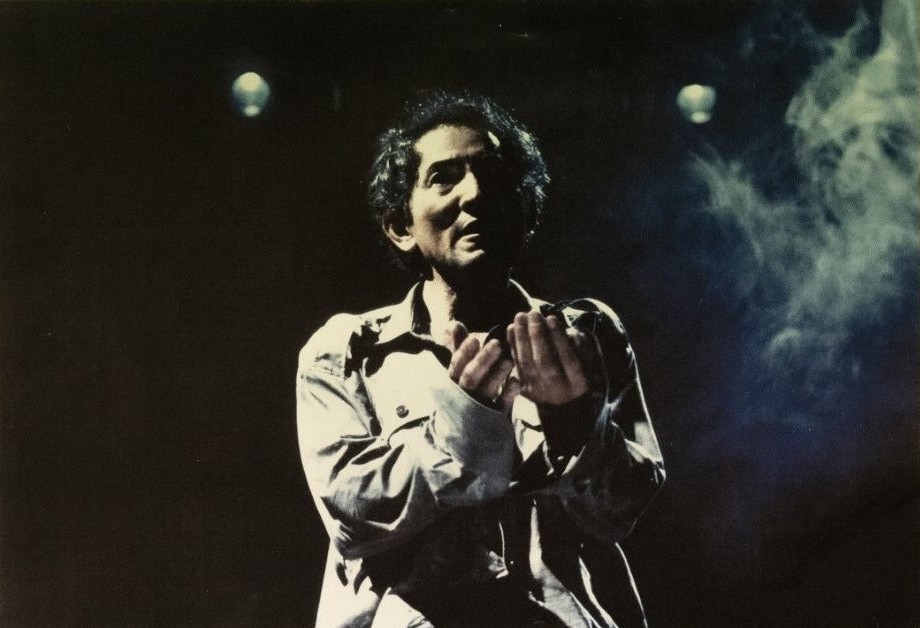

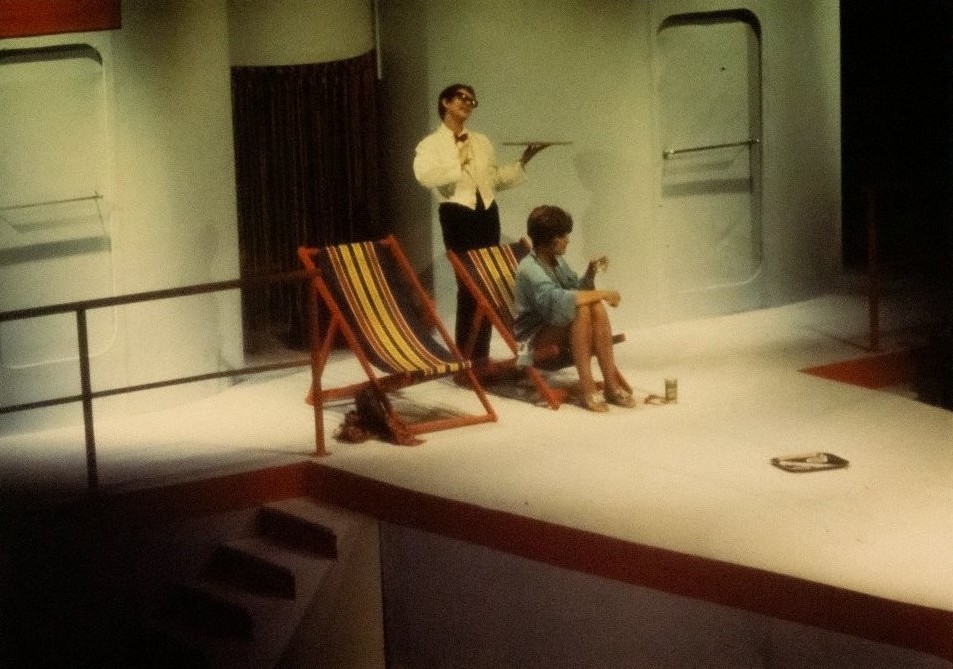

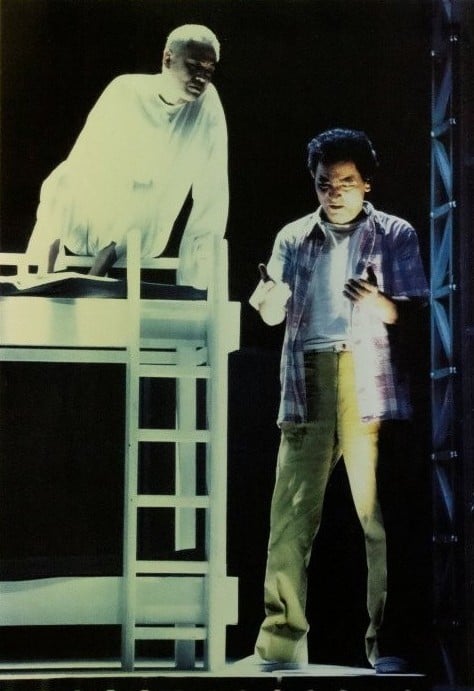

Scenes of the performance of The floating world at the Melbourne International Festival of the Arts

In exchange, Playbox Theatre performed Japanese playwright Chikao Tanaka’s Head of Mary in Melbourne. This play follows atomic bomb survivors in Nagasaki who pray to a statue of Saint Mary at a church that was destroyed by the bomb. This play attracted great attention in Australia before it was even released.

There were many war-themed plays performed to commemorate 50 years since the end of the war, so the newspaper reviews didn’t make a big deal of the Tokyo show. When we conducted a survey of the audience, the generation that experienced the war deeply sympathised with the main character. On the other hand, people in the 20s or 30s responded ‘Why now?’ I was certainly shocked at the difference in reaction between the generations.

But that was completely different to the reaction in Melbourne. Australia’s public broadcaster SBS’ news program and various newspapers came to interview me. A Melbourne newspaper released an article titled ‘A show to equal a thousand apologies: the war has finally ended.’ It apparently was quite shocking when a Japanese actor said ‘Jap!’, a derogatory word that was used by Australian soldiers.

The two interchanging shows in Tokyo and Melbourne that summer were an unforgettable experience. It was the starting point for me to begin thinking about the possibilities of translated and cross-cultural plays.

ー What kind of interactions did you have with the Australia-Japan Foundation during your various works in relation to Australian theatre and literature?

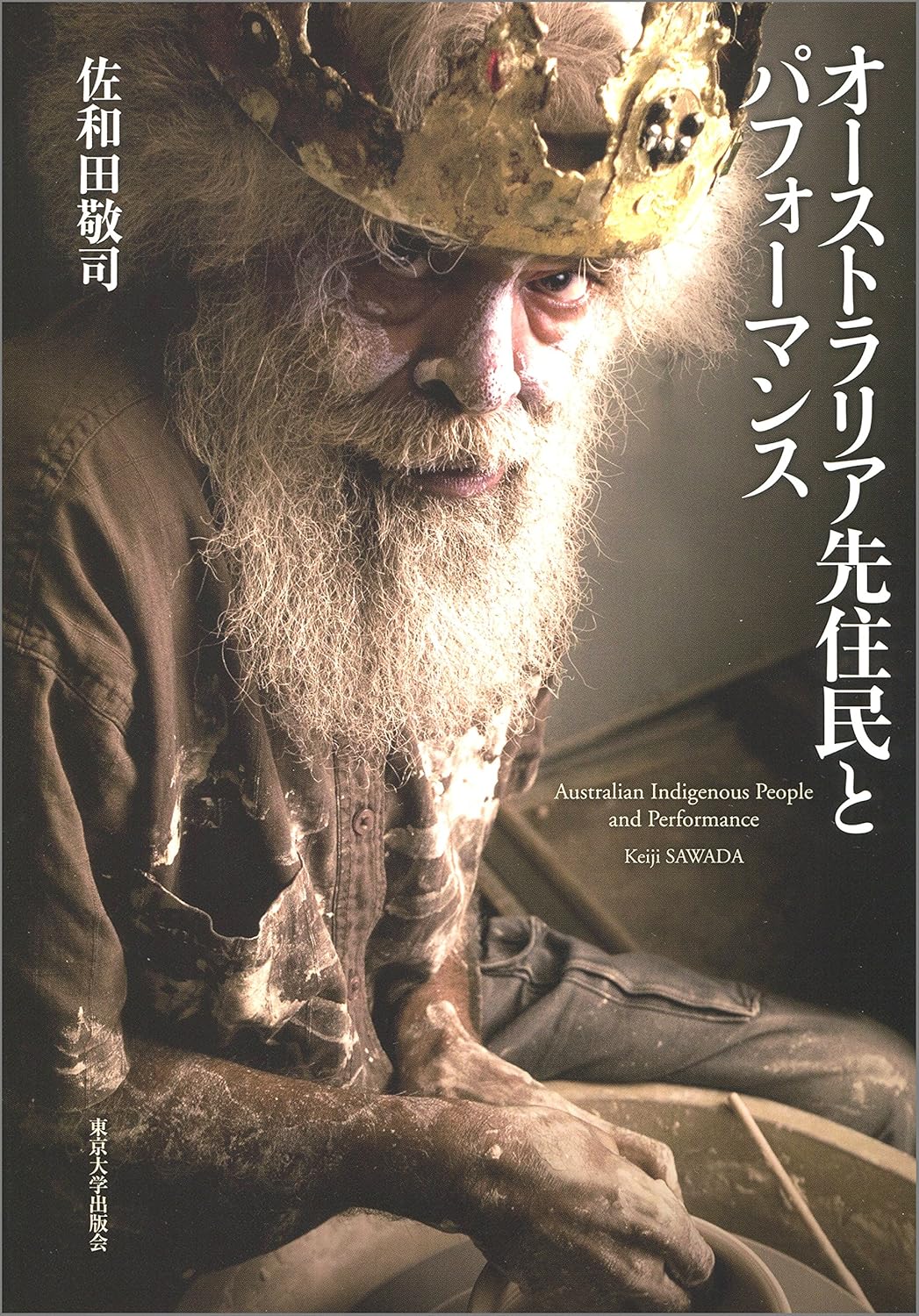

I have received a lot of support from them – from the production of my life-time work, the Australian Drama Series, to behind-the-scenes work that even I do not realise. I was able to publish Australian Indigenous people and performance (University of Tokyo Press) in 2017 with the funds received from the Australia-Japan Foundation. In this book, I explore Aboriginal people’s expression through performance as people that have lived through social and cultural suppression.

Cover of the Australian Indigenous people and performance

Also, there is a joint project to publish a book on Yasukichi Murakami – through a distant lens. This play is written by Mayu Kanamori, a photographer and performance writer who lives in Australia. It is based on a true story of Yasukichi Murakami, who travelled to Australia before the war and shined as a photographer and entrepreneur.

I learned about Ms Kanamori through a documentary movie she filmed called The heart of the journey. This movie is based on a true story of Lucy Dann, an Aboriginal woman who lived in the Western Australian town of Broome. Lucy finds out her father is Japanese after coming of age. She then meets Ms Kanamori and together they visit Taiji-cho in Wakayama prefecture on a journey to meet Lucy’s father. Many people from Taiji-cho moved to Broome before and after the war. Broome is a town that flourished from the pearl industry in the past. Japanese people initially worked as pearl divers, and eventually in pearl cultivation post-war.

After some effort, Lucy is finally reunited with her father during her first visit to a rural town in Japan. The scene where Lucy and her Japanese siblings – who all look similar to each other – engage with other despite raised in different cultures and languages is very memorable and heart-warming. The production consists of over 350 photos, audio interviews, and music. It was performed live after it was produced and aired on ABC Radio in 2000. It was performed in Japan at the Theatre Image Forum in Shibuya in 2003.

Apparently Yasukishi Murakami was a man of influence among the people who migrated from Wakayama to Broome. In the play Yasukichi Murakami – through a distant lens, Ms Kanamori created a character called Mayu – who is based on Ms Kanamori herself –to follow the footpaths of Yasukichi Murakami.

Yasukichi Murakami migrated to Broome from Japan towards the end of the Meiji Period. He initially worked at a store run by a Japanese person. He was taught photography by the store owner’s wife, and he eventually started taking photos himself.

The photos taken by Yasukichi Murakami captured a unique perspective of the lives of Aboriginal people, people of Asian background, and Japanese migrants. These photos are now very important records to understand what Australia was like back then. When World War II begun, he was captured as an ‘enemy alien’ and died in a concentration camp. Most of the photos he took and his documents were lost then.

Ms Kanamori’s play follows Mayu’s journey to find the lost photos taken by Yasukichi Murakami. She visits many places, before finally reaching his hometown, Tanami in Wakayama. Photos taken by Mr Murakami were miraculously kept there, and Mayu showcases them during the performance. The photos were displayed during the live performance, and the audience was amazed that ‘such a photographer existed’.

I was mostly touched by the fact that Yasukichi Murakami settled into the multicultural Australian society as a Japanese person and left photographic records of the society. We tend to think of Japanese people as migrating to Hawaii or west coast of the US, but there were pioneers like him that migrated to Australia.

This piece also plays a role in showing Australian audiences how Japanese people engaged with Australian society before the war. Australian people tend to think Japanese people are ‘expatriates employees’ or ‘young people on working holiday visas dreaming about surfing in Australia’ but the historical background and connections before the war are barely known. Through this piece, the audience can understand ‘Australia was not established just by European migrants, but people from many cultures contributed to shaping society since before the war.’

I think Kanamori’s play is particularly important because it uncovers the paths taken by Japanese people before the war – paths that had long been buried in history. So, in June 2022, after the COVID-19 pandemic started to settle, I held a reading performance of Yasukichi Murakami at Waseda University’s Ono Memorial Auditorium under the direction of Kae Sugata from the Haiyuza Theatre Company. We also invited Kanamori for a panel discussion. Further, in January 2024, the play was performed at Osaka University Nakanoshima Centre under a different director.

Poster of the reading performance of Yasukichi Murakami at Waseda University

Credit Chie Muraoka

Currently, I am working on a book that features the English version of Yasukichi Murakami – through a distant lens that Kanamori first wrote. The book will also feature the Japanese version performed at Waseda University and Osaka University, as well as the photographs of Australia taken by Yasukichi Murakami.

ー Do you have any hopes or goals you wish to achieve as a researcher on Australian theatre and literature?

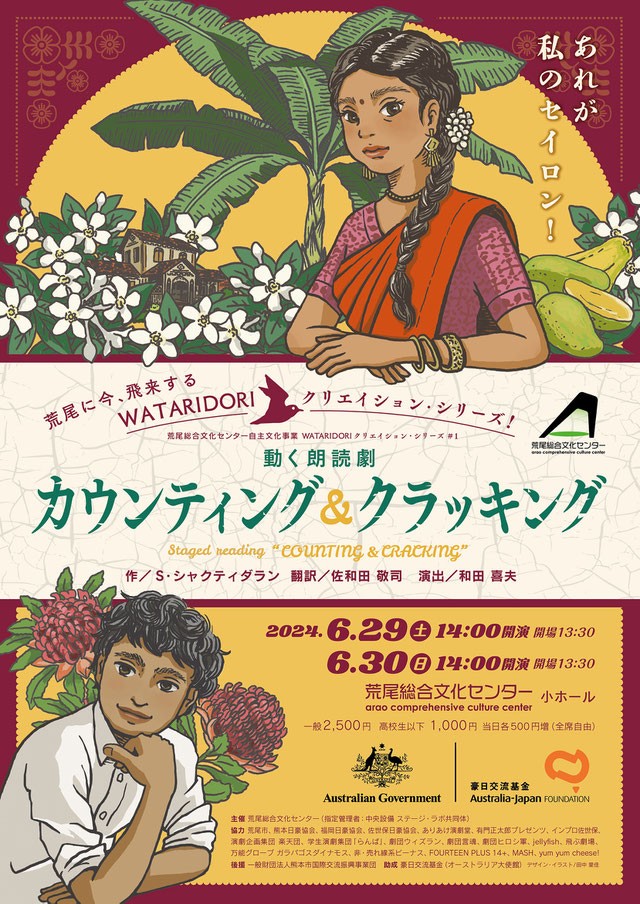

I want to promote works by Asian-Australian playwrights. In particular, I want people to know about a play called Counting & cracking. It is written by an Asian-Australian playwright, S. Shakthidharan. It really is a signature piece of Australian theatre. The playwright himself is a Sri Lankan-Australian. This story is about the civil war in Sri Lanka and a family who sought refuge in Australia.

The main character is a Sri Lankan woman called Radha. She fled to Australia during the civil war, believing her husband had been captured by the government and passed away. But her husband was actually alive and when he was released from prison after a few decades, he also arrives in Australia. Another important character is Radha’s son, Siddhartha. He is a young man that grew up in Australia and cannot speak Sri Lankan. He was uninterested in his heritage, but as he finds out about his family history, he begins to explore his identity.

Radha carried her grandfather’s ashes since she fled Sri Lanka. She reconnects with her identity as a Sri Lankan as she mourns for him. Siddhartha too begins to explore his identity as an Australian and Sri Lankan.

This piece sharply cuts into the ‘refugee issue’ – a topic that Australian society has been grappling with. During the 2000s, the arrival of the ‘boat people’ who fled from war or civil war was a major social issue. Although Australia welcomed the ‘boat people’ during the Vietnam War, there are many debates about it in the 21st century.

This piece explores this issue facing modern Australia through a family story. It was first performed at the Sydney Festival and Adelaide Festival in 2019. It attracted great interest. It was later performed in Edinburgh and New York, attracting global attention.

I personally was involved in bringing this play to Japan. Three years ago, in 2022, I hosted a reading performance at the Japan Directors Association and invited Shakthidharan for an online talk session. Then in 2024, the Japanese version was performed at a reading performance held at a cultural centre in Arao, Kumamoto prefecture, under the directorship of Mr Yoshio Wada. I think it was an important opportunity to show the power this play holds to the Japanese audience.

Poster of Counting & Cracking in Kumamoto

.jpg)

Scenes of the performance of Counting & Cracking in Kumamoto

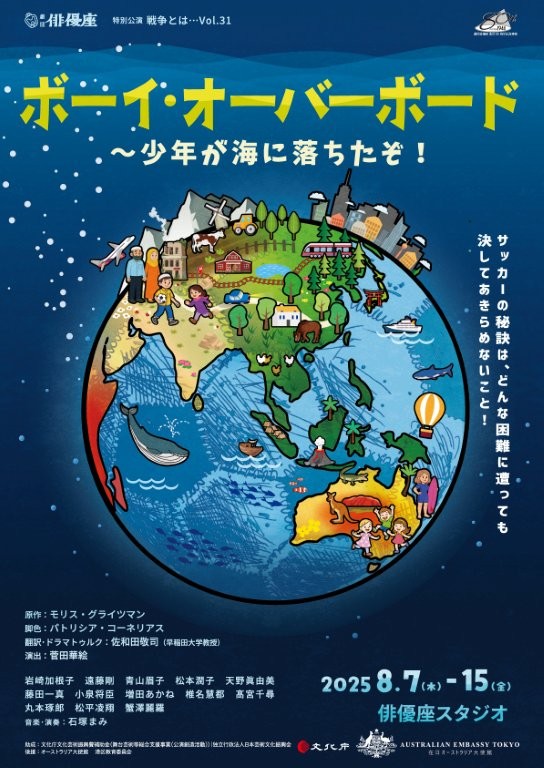

The drover’s wife – the play I mentioned earlier – was performed by Haisho Theatre Company at Ikebukuro in 2025. Australian theatre will continue to be performed in Japan thereafter; Boy overboard has been and Babyteeth will be performed by Haiyuza Theatre Company in 2025 and 2026, respectively. Let’s hope Yasukichi Murakami – through a distant lens can be performed at more locations around the country.

Poster of The drover’s wife by Haisho Theatre Company

Poster of Boy overboard by Haiyuza Theatre Company

My future goal as a researcher is to leave written records of how Australian theatre performances were received in Japan. As a practitioner, I want to increase awareness of Australian theatre in the Japanese performing arts industry. In order to do so, I hope to continue translating many new plays, and deliver them to Japanese audiences.

Keiji SAWADA

Keiji Sawada is a researcher specialising in Australian theatre, a translator, and a professor at Waseda University. He graduated from the First Department of Literature, majoring in English Studies, at Waseda University in 1990. He then completed a Master of Arts at the Graduate School of Letters, Arts and Sciences, majoring in Theatre Studies, at Waseda University in 1992. He completed coursework for a PhD in theatre studies without receiving the degree, before completing his PhD (Cultural Studies) at the Department of Critical and Cultural Studies at Macquarie University in 2005. Keiji Sawada published the Australian Drama Series (Oceania Press) (16 volumes) whilst teaching at Waseda University. Other publications include Australian indigenous people and performance (University of Tokyo Press). He received the 10th Yuasa Yoshiko Award in 2003 for his translations of Stolen, Honour and The 7 stages of grieving.