Professor Yasue Arimitsu studied at the Australian National University as an inaugural recipient of the Australia-Japan Foundation (AJF) Graduate Scholarship. Ever since returning to Japan, she has continued her research activities, having received a number of grants from the AJF.

She is regarded as Japan’s foremost expert on Australian literature, having served as the President of the Australian Studies Association of Japan as well as President of the Australian-New Zealand Literary Society of Japan. In 2002 she received the AJF’s Sir Neil Currie Award for her work Australian Identity: Struggle and Transformation in Australian Literature. In 2007 she released an anthology of Australian short stories and received the same award to support its publication. More recently, she has supervised the Masterpieces of Australian Contemporary Literature Series, which is supported by the AJF. She is also involved in a range of activities, including publishing works on Australian Studies and introducing Australian culture.

Q: Professor Arimitsu, could you please give us some background on how you ended up studying at ANU as an inaugural recipient of the AJF’s Graduate Scholarship?

A: After finishing graduate studies at Japan Women’s University, I became a research assistant in English literature. It was at that time that I became aware that the AJF was offering Graduate Scholarships, so I applied and ended up studying abroad.

At the time, I was interested in British and American literature of the 20th century, especially modernist writers. I read a lot of James Joyce, D.H. Lawrence and Virginia Woolf, as well as participated in symposia.

It was then that I was asked to translate an anthology of short stories that included a work by the writer Katherine Mansfield. Having read Mansfield in class, I knew she was a captivating writer and threw myself into the wonderful opportunity of translating her work. It was a short story called “The Woman at the Store,” which was about New Zealand during colonial times. My interest was piqued once I learnt this author was from New Zealand. That is when I heard about the Australian-New Zealand Literary Society of Japan, which I joined. I subsequently encountered the Australian writer Patrick White, who had just won the Nobel Prize for Literature, and came to like him very much. That is why I jumped at the chance to apply for the AJF Scholarship. At that time, most works of British and American authors were published in the US and UK while works of Australian and New Zealand writers were often mixed in with them to be considered a part of British and American literature.

Q: Having secured a scholarship, where did you choose to study abroad?

A: I bombarded universities with letters and thought that I would go to the one that responded first! Haha!

I immediately received a positive response from the ANU in Canberra, which is not a big city like Sydney or Melbourne, but does have fantastic libraries, making it the perfect environment for conducting research. So, I decided right away to go there.

Q: What did you study at ANU?

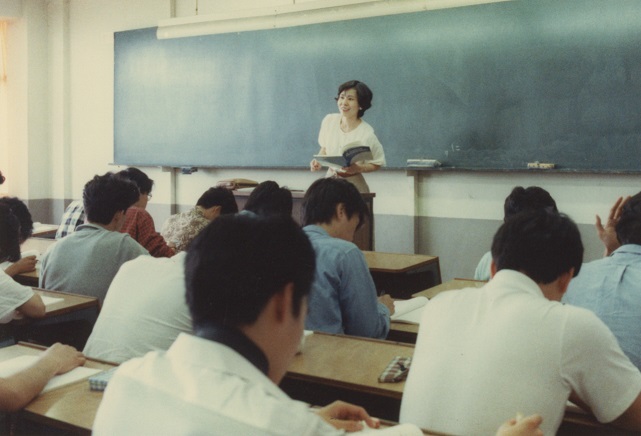

A: Actually, at that time, the ANU didn’t have a course in Australian literature. English Departments in Australia focused on British and American literature. It depends on the university, but not many people were studying Australian writers – at least not that many at ANU. For that reason, there was basically no coursework component for my graduate studies – it was purely about the thesis. So, I had to do everything myself.

Australian students were bewildered, asking me why I was interested in Australian literature. It was a time where the study of Australian literature had no standing within Australia. But, of course, Australian studies and the study of Australian literature is a flourishing field today.

Nevertheless, because I had no understanding of Australian literature, I started by sitting in on undergraduate courses on Australian history, both general and literary. I would also read books recommended to me while writing my thesis.

Q: What was the topic of your thesis?

A: On Patrick White’s early novels. As Australia’s first Nobel laureate for literature, I’d settled upon that as my topic from the very beginning, but my fellow students warned me to avoid that topic as he was so inscrutable. My supervisor also told me to write about five different works, when it was customary in Japan to focus on just one. I was in an unenviable position, but seeing as I’d been given an AJF scholarship, I felt that I had to just throw myself into the thesis and I investigated how White developed himself as an Australian writer through five of his early novels.

Q: Why is he so inscrutable?

A: White was born to Australian parents in the UK but brought up in Australia. Most of his studies were in the UK, so he was possessed of a dilemma of being an Australian writer but also drawing from the British literary tradition. For this reason, he had a strong sense of post-colonialism and suffered greatly as he produced his works, making him an extremely unique writer. His works are set in Australia but are depicted with European values. It is difficult to tease apart the complex psychological rendering of his characters, something that frustrates even Australian students of his work. That is why they tried to stop me from choosing this as the theme of my thesis. It took me a lot of time and effort, but as I worked through it all, I came to a fuller understanding of the topic and got a great deal out of it.

Q: It must have been hard to conduct your studies when there was no course about it.

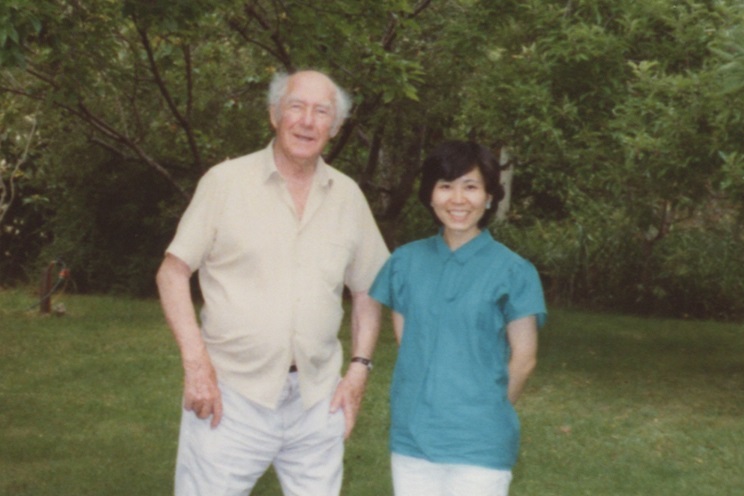

A: I was desperate to achieve some sort of result. I received advice from many teachers, and as I was the first Japanese person to study under their supervision, they were extremely kind to me. I called my professors by their first names as a matter of course, and they often invited me to their homes for dinner.

There was an Emeritus Professor by the name of A. D. Hope who playfully wouldn’t respond to me unless I called him by his first name. And this was a globally renowned poet! I was incredibly close to teachers like him. That was typical of Australian universities – this direct friendliness.

It was so long ago that I don’t really remember the difficult parts, but I do have clear memories of the wonderful parts such as this.

Q: Was there anything else that was useful to you during your period studying abroad?

A: AJF staff encouraged me to travel, saying that if all I did was study without travelling the country, I wouldn’t be able to understand Australia. Other exchange students and graduate students had to economise, with some having just enough to go out for a meal but then not having enough for transport costs home. So, I had no thoughts of travelling. But having been encouraged to do so, I travelled the country and learnt a lot about the reality of Australia. Things that I could never have learnt just by staying in my research office.

They covered all my travel expenses, which gave me some spare pocket money that I used to buy a car with my own money. That allowed me to spread my wings beyond campus and have many more experiences further afield. Thanks to the scholarship, I was able to not only pursue research worry-free, but also come to a deep understanding of Australia.

Q: Did expanding your understanding of Australia impact your research?

A: Well, in Australian literature, there is a mainstream and a non-mainstream. The mainstream is Anglo-Celtic writers whose background is the UK. The non-mainstream relates to immigrants with hundreds of other linguistic and cultural backgrounds, as well as the indigenous aboriginal people. Heading out onto the street and travelling to other regions meant that I came to fully grasp the shape of this society.

In 1973, Australia fully abolished the White Australia Policy and embraced multiculturalism. I was studying there in the early 1980s, after the end of the Vietnam War, when a great many Vietnamese people were emigrating to Australia. It was a time when the Asian population of Australia was skyrocketing. I think that I was able to get a visceral sense of this period of dramatic change – from a White Australia to a multicultural Australia – not just through literature but also in my everyday life.

Q: What specific changes did you see?

A: Well, in the field of literature at the time, for Australian students, the study of English literature largely meant the study of British and American writers. Interestingly, the only people focusing on Australian literature were foreign students such as myself.

But now, Australians are very active in pursuing research on Australian literature. Nevertheless, the question of what exactly constitutes Australian literature is very difficult to answer and is plagued by questions of ‘mainstream’ and ‘non-mainstream’ writing.

Q: If you were to take a stab at defining Australian literature, would you say that, in general, it is the mainstream that is more representative, or the non-mainstream?

A: Both are equally a part of Australian literature, which is the overall stance of Australia as a multicultural nation. There is no such thing as a stereotypical definition that can pinpoint ‘Aussiness’. I mean, it doesn’t even matter in which language a work is written.

Now that Australia is a multicultural nation, it’s normal to ask a new acquaintance what country they have cultural connections with. People of completely different cultural backgrounds are all Australian. That said, it’s not the case that all works are treated equally. There is a debate within Australia about the definition of Australian literature.

Q: In other words, setting out a definition is itself difficult given that what is ‘mainstream’ is now so ambiguous.

A: It’s even difficult to speak of trends. For example, in 1987, an Aboriginal woman named Sally Morgan wrote a book called My Place (written in English but translated into Japanese by Megumi Kato with the title My place – A story of Aboriginal love and truth), which became a tremendous best seller. However, it also caused a great uproar, given that its editor was white and that it was written in English. It was said to not be true Aboriginal literature. With the shift to multiculturalism, publishers were more proactive in publishing works by minority writers, which came to the attention of readers, creating something of a trend. But the question remains if it can be said that this equates to equality.

Q: That is a problem at the heart of multiculturalism, isn’t it?

A: Yes, it is. There was a surprising incident in 1995, relating to a novel published in 1994 called The Hand that Signed the Paper, which received stellar reviews and received a number of authoritative awards. The book was about the daughter of Ukrainian-Australian immigrants who reflected on her relatives’ stories of life in Eastern Europe during WWII. The author was Helen Demidenko, which is a Ukrainian name. The author herself clearly stated during interviews after receiving awards that she had Ukrainian heritage. However, the media later revealed that she was actually an Anglo-Celtic student at the University of Queensland by the name of Helen Darville. One point highlighted by the judges in their high praise for the work was that it was by a “writer with an immigrant background,” casting doubt over praise for the book itself. The author later apologised, saying it was a work of fiction that included fabrications over her ancestry. However, the incident stirred up debate within Australia over the fact that it had been shown that authors who are “non-mainstream” are at an advantage.

In a multicultural society that should ensure equality, the Demidenko Affair was deeply intertwined with policies for the cultural protection of immigrants and other minorities. At that time, the situation was such that mainstream works that had no cultural divergence were largely overlooked. While Helen Darville said that she did not deliberately misrepresent her work having discerned as much, the incident did raise serious questions over the criteria used to judge literary awards. Professor Arimitsu’s work Australian Identity: Struggle and Transformation in Australian Literature, which examines how this mainstream author with a western background misrepresented herself as having a non-mainstream background, won the AJF’s Sir Neil Currie award in 2002.

Q: What sort of Australian literature are winning awards today?

A: Looking just at the works themselves, there are many where the nationality of the author is not clear. In an age of globalisation, we see similar things happening in other countries as well.

For example, the novel The Boat (2008; translated into Japanese by Takayoshi Ogawa), which has received numerous awards both inside Australia and abroad, is by Vietnamese-Australian author Nam Le, who lives in the Unites States, and published that work there. His stories have not necessarily been set in Australia.

Q: So, that means you can’t ascertain if a work is Australian literature or not without reference to the author’s profile?

A: Yes, that’s true. Literature is in flux at the moment, and identity is no longer required. For example, when Yasunari Kawabata won the 1968 Nobel Prize for Literature, his works were praised as being very Japanese. However, in 1994, it is said that selection panel members were impressed by Kenzaburo Oe’s use of a very European style of expression. You can see that what panellists value has changed over time.

As such, it is nonsense to ask of Australian writers that they have an Aussie identity. I think globally there is a shift in literary evaluation.

Q: Globalisation of culture is progressing around the world, and Australia is at the forefront. What aspects of Australian literature are you most excited about?

A: Perhaps just this complexity. One cannot speak of Australian nationhood, race or national identity in simple terms. These are truly difficult topics. I think the best aspect of Australian literature is that it allows us to enjoy differences with our own cultural background and ways of thinking.

Q: So, you’ve moved from researching Patrick White’s struggles with finding his own identity, to living in an era where identity is superfluous. What a fascinating journey!

A: When I got the AJF scholarship and went to Australia for the first time, I was enthralled by how different Australian literature and lifestyles were to Japan. I was motivated by a desire to live abroad and experience all that was foreign.

I was able to extend my stay by another year, and ever since my return to Japan I’ve visited Australia on practically an annual basis. I’ve seen with my own eyes how Australia – its cities and its literature – has transformed itself. Every time I notice we have reached a historic milestone my passion is reignited. That I had the chance to study abroad and pursue research is very much thanks to the AJF, for which I am most grateful.